The Slums to Come

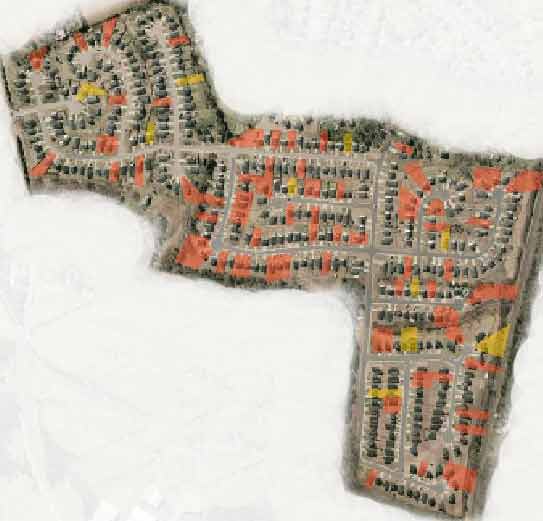

This neighborhood is doomed. It's only five years old, a new

subdivision on the suburban fringe of a booming sunbelt city,

made of relatively inexpensive starter homes. The properties in red and

yellow are recent and pending foreclosures, all of them now vacant. The

people who live here don't know what hit them. Suddenly, right after

they bought their dream homes, others on the block started to

empty out. Then crime and gang activity appeared, the last

thing they expected.

No one's looking after the vacant homes now; frazzled homeowners are jangling the phones at city hall, demanding action, only to be told that city police and service crews are busy; their neighborhood isn't the only one. For Americans who get their news from the mainstream media, the subprime crisis that surfaced in the late summer of 2007 came as a complete surprise. Even now, when it has become evident that something extraordinary is occurring, the nation seems to shambling through the crisis bemusedly, as in a dream. Right now, the media has more important

things to trouble its beautiful mind. There are foreigners with bombs,

and inexplicable wars, and political campaigns and a great waving of

banners and bunting. The great hypnotic eye that hovers over Washington

holds us all spellbound, and the things that should matter most to us,

matters close to home, have to wait patiently in the corner and not

speak until they're spoken to. This is only the beginning. We're a nation of gamblers, and every state and region knew real estate booms and busts as it was growing up. The bursting of the speculative housing bubble in the great Crash of 2007 is unique, dwarfing anything that came before in it. The subprime scandal—and scandal is the word for it—was only the match that touched off a national explosion, a cosmic belch ofrotting, indigestible debt that will be perfuming the United States for a long time to come. A colossal bloc of adjustable-rate mortgages is coming due for a rate jump in the first six months of 2008. The total value of these resets is expected to be over a half-trillion dollars. Bankers around the world are waiting for that money to shore up their teetering balances, and right now it looks like they can just go whistle for it. A financial analysis from thefirm Global Insight, in an study for the National Conference of Mayors, predicts at least 1.4 million homes will enter foreclosure next year. The total number of foreclosures from subprime mortgages alone should eventually top two million. Since the speculative bubble burst, house prices have been dropping all over the country. According to Business Week, if prices drop another 20%, two thirds of all the nation's homeowners will see their equity completely wiped out. The chances are good. A recent Goldman Sachs report forecasts a dive in California as deep as 35-40%. A lot of these people have run up big credit card debt too, and now they will have no collateral for any new loans to get them back on their feet. We might well end up with a 'third of a nation', in that phrase President Roosevelt once used, either renting or squatting in homes that they or people like them used to own. It's not as if we had no warning. Gale Cincotta of National Peoples' Action, the leader of the fight against neighborhood redlining and disinvestment in the 70's, was sounding the alarm back in April 2000: 'Subprime lending is the Wild West of the mortgage market right now. Unless we regulate the interest rates and fees that subprime, high-interest-rate lenders can charge, more families are going to lose their homes and more communities in the city and suburbs will have abandoned buildings.' Local news sources—mostly the alternative free weeklies—picked up on the growing problem in the years that followed. By 2006, even the Washington Post had heard about it. The mainstream media didn't care much for the term that Ms. Cincotta and others used—predatory lending—though it would be hard to find a term more precise. Lenders eager to expand into new markets found little remaining to them except the more precarious part of the working class, and they assiduously mined it for profit. Past generations of green eyeshades had made loans with the intention of seeing them through to the end of the contract. It was the federal government, buying up mortgages through Fannie Maeand Freddie Mac, that taught them how to expand their profits by 'securitizing' mortgages: selling them in bundles and then using the proceeds to write up new ones. Now, banks and private investors were getting in on the act too.They found subprime loans especially attractive because of their high interest rates, which only encouraged mortgage firms to write more of them. In the casino atmosphere of the last two decades these mortgage securities were especially valued as collateral. They allowed players to make even bigger wagers on stocks. Looking back, there is little indication that anyone ever worried about risk—though a lot of these stock bets are probably being called right now. The money everyone played with had been extracted from hopeful families of modest income. Trapping the greedy and gullible is how Wall Street makes a living, but in fact the whole housing industry, playing its own games, had come to depend on them too. Though merely the lowest rung of the ladder, their participation—as buyers of homes belonging to others who wanted to move up a rung—was necessary to make the whole upward-moving housing chain work. Whenever the components of the housing industry find themselves in a jam, they team up with politicians to get the feds on the case, and the result is the Housing Act of 1937, or of 1949, or 1965, or perhaps of 2009. But the progressives who believe that only Washington can sort out this mess haven't been paying attention. Washington does not fix housing messes. Washington creates them. Besides fostering the securitization of mortgages, the feds have left their fingerprints all over the subprime caper. Many of the defaults so far have come from the FHA's 'Gift Program', in which that agency put up down payment money for people who couldn't even meet that basic requirement of a sound mortgage. This well-meaning scheme made high default rates inevitable. Anyone familiar with the struggles of inner-city neighborhoods and neighborhood groups will find the current disaster all too familiar. Back in the 70's a similar crisis erupted, one that flew under the radar because it affected mostly poor, minority areas. This time the fault was entirely Washington's. The Nixon administration's HUD program known as 'Section 235' has been called the 'biggest housing scandal in history'. The admirable intent was to increase minority homeownership. But what happened on the streets was a tsunami of collusion between corrupt HUD appraisers and corrupt local builders and realtors. Hopeful working people were tricked into buying shacks with cosmetic repairs, under financial arrangements they could never fulfil. At one point in 1976, the city of Detroit alone counted 17,000 abandoned homes with HUD possession notices nailed to the doors. If you were around in the 70's, you'll remember those inner-city streets that all seemed to consist of half nicely-kept homes, and half boarded-up ones. You probably thought that the place had become so rough no one could stand to live there anymore, and it would have been difficult to understand that a vacant and vandalized house meant, like as not, your tax dollars at work. This time around, the private sector gets most of the credit, with Uncle Sam largely reduced to resisting reform, while funnelling vast sums of newly-printed fiat dollars to keep the machinery lubricated. But Washington as always finds no end of devilry to make subprime victims' misery complete. Over the last few years, some of the wide-awake states have been passing anti-predatory lending laws; New Mexico in particular did a lot to protect homeowners. Washington doesn't like that sort of thing, and there are already rumblings about a 'standard' federal plan for regulation, which would preempt any real protection for homeowners from the states. Washington made its intentions clear over the last few years. Forty-nine states have already passed some kind of protection, and asGovernor Spitzer of New York pointed out in a recent, furious essay, the administration's Comptroller of the Currency cancelled out all their efforts, bizarrely claiming overriding authority through an obscure (and most likely unconstitutional) clause of the Banking Act of 1863. Showing the same iron determination that has won it so many successes abroad and at home, the administration persisted even against the unanimous protests of 50 state attorneys general and 50 state banking superintendents. The number of foreclosures directly attribuable to the Bush administration's obstruction will reach the hundreds of thousands. From most reports, you'd get the impression that the subprime mess is only a problem for aging inner cities. It sure isn't, and that is what makes this burst bubble different from anything that's happened over the last few decades. Here are some sad stories from the suburbs that have been turning up in recent news reports: In Elk Grove, California, outside Sacramento, the median family income is over $70,000. Over 10,000 new homes were built here in four years during the housing boom, most of them lookalike tan stucco boxes in the California manner. Money Magazine rated it one of the 'best places to live' in 2006, but it ain't so great in 2008. Parts of Elk Grove now see widespread abandonment and skyrocketing crime, graffiti and gang activity. The school district, lately one of the fastest-growing in America, now faces a decline in enrolment. In the worst-hit neighborhood, housing values have already dropped by almost a third. Elk Grove did give the nation a chuckle when two of its foreclosed houses caught fire recently. The firemen found they had been converted into indoor marijuana farms, spliced illegally into the power grid (bad wiring caused both fires). A neighbor praised the unknown dopers to an AP reporter; 'The pot growers, they mow their lawns, they take out their garbage.' Today, even in the suburbs, one can't be too choosy about one's neighbors. The South has its share of subprime too. In prosperous Charlotte, partly-abandoned subdivisions are popping up all around the periphery. The worst parts are concentrations of new starter-home subdivisions, mostly on the North Side, In some neighborhoods, crime has shot up 33%, while young first-time buyers are getting reacquainted with the gangs and drugs many of them thought they had just left behind. In Las Vegas, itself one of the great bubble economies in all human history, speculators from all over the world were flying in to flip and re-flip new properties a year ago. Today house prices in some neighbourhoods values are already down 25-50% from the height of the boom in 2006. Concentrations of foreclosures turn up in surprising places, such as Aliante Silverstone Ranch, a master-planned community built around golf courses. One real estate man says there are 12,000 vacant homes in town right now, and it's just the beginning; it could be an avalanche in years to come. Think it can't happen in Vegas? Nothing in America is more transient than the sites we devote to entertainment for the masses. Most of the beautiful amusement parks set up by the old streetcar companies a century ago lasted only two or three decades. The first generation of post-Disneyland regional theme parks is already seeing its first casualties. And look what happened to once-golden Atlantic City and the other fleshpots of the Jersey shore. Right now the Vegas boosters are touting their empty houses as an opportunity, not a problem. They claim 113,000 new workers will be pouring in to fill entertainment jobs over the next few years, all looking for a place to stay. If you believe that, in this coming recession, they have a genuine Eiffel Tower they'd like to sell you too. In downtown Cleveland, the kind volunteers who look after the homeless are wondering where they've all gone. The streets around the big shelter on the downtown fringe are empty at night, and the people who used to camp there and under the bridges in the Flats have evidently found some place better to spend a Lake Erie winter. Also in Cleveland, a federal court recently tossed out a bundle of foreclosures filed by the Deutsche Bank, which happens to be the biggest holder of subprime calamities in the city. Judge Christopher A. Boyko found that the Germans could not prove title to the properties. As brokers securitized their subprime mortgages, and the bundles were passed back and forth between various financial interests and their shadowy subsidiaries, arrangements became so complex that on one actually knows who owns countless properties coast to coast. Legal fights could go on for years, and with a lack of clear title large-scale squatting might well take hold in America as it did in Europe in the 70's. Some of the results of the Great Crash we can guess: some neighborhoods are going down, and a lot of lives are going to be ruined. Inevitably, there will be unexpected consequences. Here's one for starters. In the Inland Empire, they're already worrying about a possible outbreak of West Nile virus. A lot of the people who walked away from houses they were losing walked away from full swimming pools too; the mosquitos, like the squatters, think it's heaven. There will inevitably be bailouts, shoring up some of the financial bad actors responsible for the mess, but they won't come free. Congress has a habit of attaching strings to its Wall Street bailouts, and already, proposed legislation would make the lenders responsible for the creditworthiness of their loan customers. There will be lots of forms for everyone to fill in. More importantly, if regulation goes too far it could make it hard for lenders to serve any low income people in the future, and that would be the most ironic outcome of all. Besides the unexpected consequences, there are some eminently expectable ones. Finding them requires no crystal ball gazing; the rules of American development and American decay are known and understood. In fact, they're pretty obvious and they rarely vary. Most of the threatened suburban neighborhoods mentioned above have one thing in common: they're low-end housing, what the planning department of a suburb on the make will call 'starter homes' and government reports refer to as that elusive quantity, 'affordable housing'. When government or business or a dark cabal of the two dreams up new tricks to play on communities, it's usually affordable housing that suffers first. Because of vacancies and the overall drop in home valuations, local governments in these suburbs will have a lot less money to spend, in a time when the need for services will undoubtedly be rising. In the boom years, they were able to increase services without raising rates, thanks to increasing property values. Once an American neighborhood starts to decline, it doesn't stop. As the backwash from the Great Crash pulls suburbs down, there will be tremendous pressure to turn the bigger boom-era homes into flats. Today, most of these suburbs use spurious zoning techniques to keep multi-family out—forbidding non-family members from residing in someone else's home, for example, or capping the numbers of rental units allowed in a neighborhood. But once a McMansion becomes undesirable to the sort of people who can afford to keep it up, suburban governments will be faced with the choice of letting it get carved up, or watching it become vacant and vandalized. In the 30's depression, that is exactly what happened to thousands of those charming 1880's Queen Annes on the boulevards. Roominghouses, perhaps, are the fate McMansions were born for Within twenty years, we can

look forward to an impressive eruption of low income people into fringe

suburbs—into the kingdom of sprawl. It won't happen at the

same time or the same rate everywhere. Some cities will come out of it

in good shape, others not so good. The Harlem bubble began to collapse under its own weight about 1901, and the 1904 recession finished it off. 1905 saw a big wave of foreclosures. Desperate property owners gamely tried to defend their investments, but they couldn't restrain some of their brethren from drastically lowering rents. Nobody else wanted their houses, but fortunately for them the first trainloads of blacks were on their way, fleeing the apartheid and lynchings of the South in the first wave of the Great Migration. A wave of panic selling and racial turnover crawled relentlessly, block by block. According to Gilbert Orofsky, in Harlem, the Making of a Ghetto, by 1914 Harlem had become the 'most luxurious ghetto in the world'. Rents stayed high, and the absentee owners reinvested little. After a decade or two of that, Harlem no longer looked quite so luxurious. Harlem wasn't alone. Much the same thing happened on the South Side of Chicago, after a speculative boom that preceded the 1893 Columbian Exposition. That is how the 'Black Belt' was born. Neighborhoods on Detroit's northern edge got a dose of it in the 30's, and smaller, less dramatic versions occurred in cities all over the northeast. A story as dramatic as Harlem's is rare. But all of the elements are in place today for new versions to mutate, including a burgeoning population of immigrants who, for a while, will find their new life in Sprawlville captivating. In events like 1900's Harlem, the kingdom of the poor reached out from the downtown fringes and began colonizing the new zones, the streetcar suburbs. Today, we're witnessing its breakout into a new scale, that of the automobile suburb. In the flyspeck metropolises of the sunbelt, the slums are going to be enormous. Whether or not a corner of Sprawlville becomes a slum depends on thesuccess of the people in it, and their odds for the near future don't look good. Living in a freshly-minted slum will not help their chances at all. Let's get our definitions straight. A neighborhood full of poor people is not necessarily a slum. In America, a slum is a place where a homeowner builds no equity, and a lender or a businessman can't imagine a profit. The wider community is long past caring about its schools, its safety and its social cohesion. A slum is an affliction, for which the only cure is escape. Occult collusion between government and business often makes the difference between a poor neighborhood and a slum. And all the poking and prodding of the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development has only succeeded in helping slums spread. We need a new approach. Our current system of urbanism, the same one that served us so well in frontier days, when cities were growing up, has become a monster that gobbles up raw land on one end and shits out slums on the other. As we watch new slums spreading across suburban miles, we might reflect that now, finally, those rules must be changed.

photo by jackson

|

|