035 organizing the city

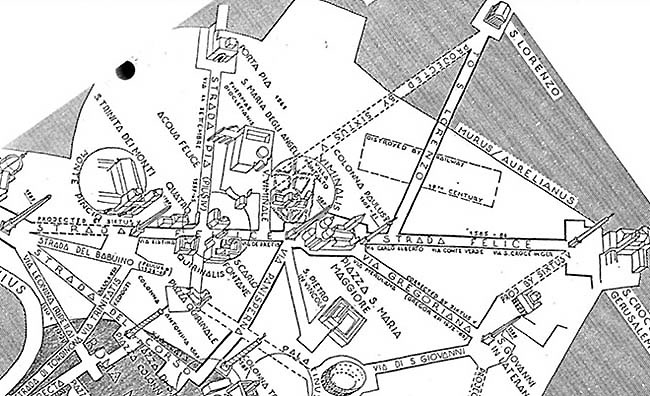

Rome, Piazza del Popolo

What ties a city together? What makes it possible for you to carry an image of a big sprawling town in your head, and find your way around in it without resorting to a map? In an American city, a strict street grid does this job quite well, in a prosaic and utilitarian way. Try and get lost in Manhattan, above Houston Street. You can't. On the other hand, as the cab driver said to Frank Sinatra and Gene Kelly in On the Town, when the cops were after them: 'I know a little place just over the river where nobody will ever find us'. She meant Brooklyn, of course, that famously unnavigable borough. Brooklyn has a grid too—or rather lots of little grids, superimposed by developers over an older network of meandering country roads. With a score of different neighborhood street numbering systems, and few nodes and landmarks to provide visual clues, the borough laughs at any concept of order. Thomas Wolfe once wrote a short story called Only the Dead Know Brooklyn You don't need a strict grid to create order, though. Take Paris. There's one grand axe, a die-straight line through the Louvre, the Tuileries, Place de la Concorde, then down the Champs-Elysées and under the Arc de Triomphe, and finally La Défense. Add in the other elements: the river, the ring of grands boulevards that follow the line of the medieval city wall, the other boulevards laid out under Napoleon III, and you have an urban image that is concise yet elegant—order, one might say, on a higher level. We don't know a lot about how ancient designers approached this task; outside of Rome, not enough of the urban ensembles remains to permit large scale reconstructions. From contemporary accounts we do know quite a bit about Antioch, a carefully-planned Hellenistic-era foundation that became undoubtedly the swankest city in the whole Roman Empire. Antioch's grid included two great covered streets, lined their entire length with colonnades and awnings, and meeting in the city center. Antioch at its height may have had a million people or more. Medieval cities were much smaller, and the simple design systems of central piazzas and streets leading to the gates was generally good enough, both aesthetically and practically. But as cities grew bigger in the 1400's and 1500's, rulers and architects began to consider planning schemes to catch up with growth. Rome, especially after the election of Pope Sixtus V in 1585, would be the leader. The Eternal City provided some unique problems. The shrunken city of medieval times could hardly fill the space contained within its ancient walls. Pilgrims from all over Europe came to make the rounds of the 'Seven Churches'; these holy sites with their surrounding settlements were at the time more like small villages, spread across a landscape of ruins, fields and gardens. Pope Sixtus meant to knit the ancient fabric back together. He had lots of cash, and the best architects of the Late Renaissance at his disposal, but much of the plan may well have been the idea of the Pope himself.

In essence, the plan was to connect the Seven Churches and other important sites, using a system of new streets and piazzas. The latter would be punctuated by Egyptian obelisks, which had been brought home by long-ago emperors and now lay around the city waiting to be re-erected. The above illustration (north is to the left) shows how Piazza del Popolo, at the main gate, Porto Flaminio, was the key to the design. Entering the gate, a traveller has all Rome spread before him: one road to the left for the Quiriinale and S. Maria Maggiore, one in the centre (Strada del Corso) for the Capitoline Hill and the city center, and one on the right for the Campus Martius and Vatican. Other new streets, including the recently completed Strada Pia, would tie in to the other churches, each with its piazza and obelisk. After Sixtus, western cities would develop any number of unique ways of organizing themselves, specific to time, place and circumstance. Architects worked the Roman lesson into plans for entirely new cities: St. Petersburg, Mannheim, Germany, and of course Washington D.C. Others employed the principle to make sense out of existing ones. John Nash's Regent Street plan created a new spine for West End London, while Baron Haussmann's system of new boulevards transfigured Paris. The biggest cities led the way in this process of discovery; capitals and industrial centers in the 19th century grew to sizes previously thought unimaginable, and the job of organizing their physical form became a crucial one.

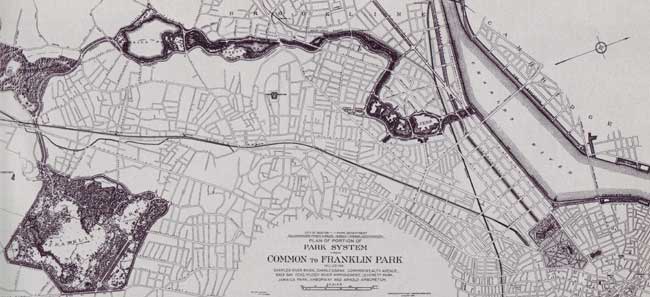

The 19th century also saw a distinctly American contribution to the process, the network of parks and parkways. It is no surprise that this would appear in our more spacious urban scenes-and trees were always the prime amenity in our early cities. The origins are obscure. Precocious Chicago was talking about connecting its new parks with residential boulevards as early as 1849. Work finally began in 1870, and the city hired Frederick Law Olmsted to oversee it while he was still busy with Central Park in New York. After that, Olmsted took the idea to Boston, and expanded it into one of the triumphs of American design, the chain of parkland known today as the 'Emerald Necklace' or the 'Fenway'. Olmsted cleverly connected the new system to the work of the previous generation of Bostonians by starting it at the end of the Back Bay's Massachusetts Avenue, near the new Charles River Basin. When it was done, the Emerald Necklace stretched over seven miles, from Boston Common to Franklin Park in Roxbury. Other cities picked up the idea from there; before World War I Kansas City, Minneapolis and Denver initiated magnificent and complete park/parkway networks, while most progressive cities got at least the rudiments in place. Cleveland extended the idea to a metropolitan level, building an 'Emerald Necklace' of its own, a system of natural preserves and connecting parkways that completely encircles the city and inner suburbs, now including over 20,000 acres. As rationalist planning elbowed out design planning in the 20's, the ideal faded; one of the reasons our newer suburbs look so drab and undistinguished today. A new generation of planners devoted itself to organizing the city in a different way, redesigning it to enable quick transport to all points by automobile. Building the urban interstates could have been an excellent opportunity to knit together the far-flung metropolis of the postwar world. Look at what we got instead, and you'll begin to see the difference between organizing the city in the fullest sense, and merely creating a transportation system. The highway engineers who created the urban interstates promised Americans parkways, in the sense that Frederick Law Olmsted would have understood, but their primitive design standards ensured that their roads would usually be eyesores instead. Neither did the engineers give any thought to the urban fabric while they were planning the routes. Instead of helping to define and improve the neighbourhoods they passed through, the Interstates often destroyed them. |

|