230 city beautiful

The return of

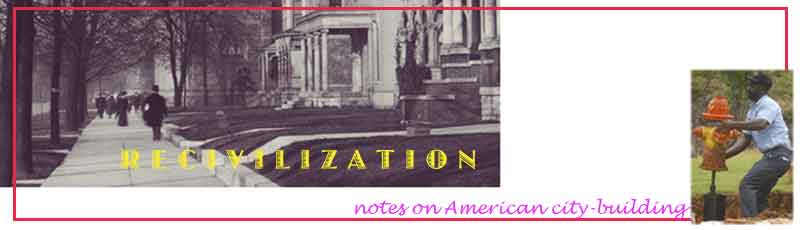

formal design in America: a souvenir book from the World's Columbian Exposition, 1893.

President Grover Cleveland opened the festivities by pushing an electric button, illuminating at once some seven hundred acres of Beaux-Arts architectural fantasies. The World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 was the biggest fair ever, covering ten times the area of Paris's in 1877. Young Chicago raised up four hundred buildings for the 'White City', with the collaboration of the greatest names in American architecture and landscape design, including Frederick Law Olmsted and a rising star named Daniel Burnham. There were moving walkways, strings of incandescent bulbs, and a Women's Building, designed by a woman architect and decorated with murals by Mary Cassatt. On the international Babylon of the Midway Plaisance, visitors could inspect the Dahomeyan Village, a camp of South Sea Islanders or a Street in Cairo, set among the carney barkers, the cooch dancers and the world's first Ferris wheel. Frank Lloyd Wright came, and from the architecture of a transplanted Japanese temple he gained a lasting inspiration that would find its way into his Prairie houses. A Detroit mechanic named Henry Ford came to see the four cars on display, including the only internal-combustion model, an imported Daimler. The biggest building was devoted to manufactures; it covered 25 acres, with exhibits ranging from naval guns to the latest in flush toilets. One manufacturer brought a giant model of the Brooklyn Bridge, made of its soap cakes. Others gained attention by introducing new products, from Shredded Wheat to Cracker Jacks: the fair also witnessed the popularization of the hamburger and soda pop. As much as 10% of the U.S. population may have come to Chicago for the big show. They saw the future, and they knew it; America would never be quite the same again. Those who who could not experience it in Chicago would get other chances closer to home in the wave of imitation expositions that followed: Buffalo in 1901 (where Mc Kinley was assassinated), St Louis in 1904, not to mention the 1897 Centennial Exposition in Nashville, a passable copy of the White City with that famous concrete Parthenon for a centrepiece. Henry Adams called the White City 'the first expression of American thought as a unity', but what people found inspiring about Chicago was not so much the industrial triumphs, the carny shows or the gadgets, but the White City itself, the vision of a beautiful, harmonious world conjured up by a community that hadn't even existed sixty years before. It occupies such a conspicuous place in our history not as a cause of what followed, but as a symbol— the promise of an America that had reached maturity.

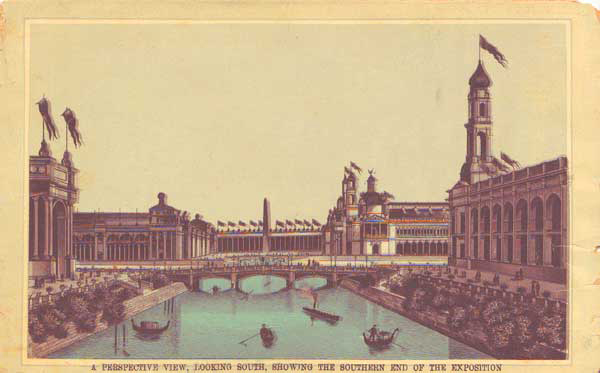

Sixteen years after the Fair, Daniel Burnham published the Plan of Chicago

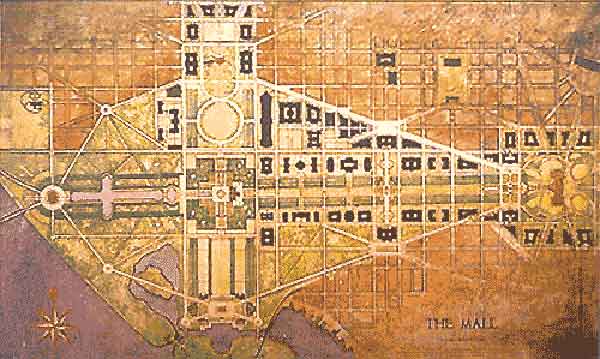

While the 90's depression held up plans and discouraged new initiatives in other cities, Chicago kept on planning and building. The momentum continued directly after the Fair, with Burnham's plan for the South Park Commission in 1896. Burnham, the man of the hour, settled into his role as America's first complete city planner since colonial times. Besides providing the vision, he symbolized the sort of man needed to push things through in the new organizational world; he knew how to line up the big names and keep them moving in step. Burnham took some time off from Chicago to oversee plans for Washington, San Francisco and Manila before recalling his attentions home for the most ambitious and comprehensive scheme ever seen in America, the 1909 Plan of Chicago, on which he worked two and a half years without pay. Chicago wasn't fooling. The Commercial Club, pushed along by its vice-chairman Charles Wacker, initiated and financed the plan, and Wacker found a top-flight promoter from the Chamber of Commerce named Walter Moody to spread the good word. His steamroller campaign included a team of lecturers with hand-tinted color projection slides, a motion picture, a book of suggestions for the clergy on how to promote the plan in sermons, and a boiled-down version of the plan called the Wacker Manual that was reprinted for decades as a textbook for every eighth-grader in the Chicago schools. Happily, Moody had a great product to sell. Inspiration comes most often when vision and utility coincide, and that is exactly what Burnham and his backers gave Chicago: not just urban design, but city-building in the fullest sense of the word. One image sticks in the mind of anyone who has ever seen the Chicago Plan, the aerial view of the future city showing a lakefront transformed into parks, with a ring road and a network of arterials converging on an imperial-scale civic center. Visual order is manifest, symmetrical and beautiful. At the same time this order systematized the city's street traffic pattern, as well as its freight traffic, and it tied surrounding towns and villages into an efficient, integrated region-a major goal of the Plan, framing the city-state that Chicago Tribune editorialists would soon be calling 'Chicagoland'. Chicago's big shots, led by the Commercial Club, followed the Plan like a Bible; within 15 years they spent the then-incredible sum of $300,000,000 on plan-related improvements: the lakeshore parks, the two-level Wacker Drive and the Chicago River bridges, museums and other institutions, road improvements, Union Station, Navy Pier, the Forest Preserves. The one major element of the Plan Chicago never undertook was the overwrought and expensive civic center (the huge central square in the illustration above).

Other cities were willing to try and reproduce the dream of white domes and colonnades first seen over the blue of Lake Michigan. So was the U. S. Congress, which called in Burnham in 1901 to redesign the Capitol Mall and Potomac riverfront. Restoring Pierre L'Enfant's vision, by redeeming the Mall from the jumble of little parks, depots and rail tracks it had become, proved almost as much of a revelation as the fair. Burnham's 'McMIllan Plan', so called for the Congressman from Michigan who took charge of the matter, caused a sensation when it was unveiled in 1902. The best parts of it were accomplished with dispatch, and most of the worst left out, leaving an expansive and harmonious ensemble, orderly and monumental without bluster or arrogance. Once the Lincoln and Jefferson Memorials were in place, the new Mall was perfect; it still tells Americans as much about themselves and their aspirations as words could ever do. In Cleveland, Tom Johnson called in Burnham in 1903 to create a design for a long-discussed 'group plan' of public buildings, and he made it the most ambitious of the City Beautiful civic centers, built around a generous open space that would come to be called the 'Mall' in emulation of Washington's. Chicago's effort had been the businessman's, Cleveland's an expression of radical democracy. In the following year, 1904, Denver showed that equal results could be obtained from a political boss. Mayor Robert Walter Speer, calculating politico, practical real-estate man and earnest tree-hugger, began what might be the most satisfactory of all the civic centers, framed around the golden-domed state capitol. With the aid of Charles Mulford Robinson, the leading publicist of the City Beautiful movement, Speer also fostered an admirable system of parks and parkways; Denver is justifiably proud of them today. Not all such efforts succeeded. On the west coast, a grand but poorly-conceived civic center effort in Seattle failed completely. San Francisco, with much of its center in ruins after the 1906 earthquake, and with an exciting comprehensive plan by Daniel Burnham ready to go, chose instead to rebuild itself on the old lines, just as London did after the Great Fire of 1666. Eventually, the city did build itself a handsome civic center, but the biggest opportunity in its history had been lost.

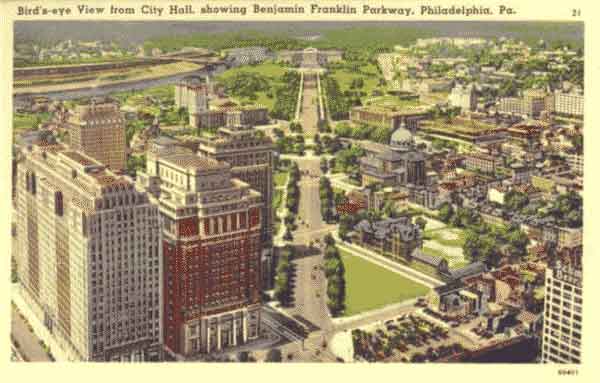

In Philadelphia, the showcase improvement was not a civic center, but the Fairmount Parkway (1903-14; now Benjamin Franklin Parkway), a majestic diagonal boulevard slashed through Penn's grid with the City Hall tower at one end, and the new Philadelphia Museum of Art sited to close the view on the other. One of the most creative of all City Beautiful plans, the Parkway remains a model for finding an beautiful solution to a practical traffic problem. This happened to be the work of a Frenchman, Jacques Gréber, but elsewhere, the City Beautiful aesthetic put American architects and planners in demand overseas for the first time. After Chicago's, the biggest and most striking of all City Beautiful designs was Walter Burley Griffin's plan for Canberra, the new capital of Australia (1913). City Beautiful was fortunate to have an extremely talented generation of architects in its employ. Men like Burnham were instrumental in guiding and promoting the effort—retaking some of the authority in city-building they had lost to landscape architects. They were in control of the movement, and their influence had never been greater. Under the influence of the Beaux-Arts, classicism had already taken root; Chicago only confirmed it (the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, a relic from Napoleon's time, was the national academy and school that all French architects had to attend; its classicizing manner was brought to America by such students as Charles Follen McKim). The men of the time saw its advance as a sign that America had reached a sort of cultural parity with Europe, and in truth the Americans were handling their borrowed fashions with a grace and authority old world architects seldom reached. They raised a crop of some of the finest public buildings in our history: Cass Gilbert's Detroit Public Library, and his state capitols in St. Paul, Minnesota and Charleston, West Virginia, George B. Post's in Madison, Wisconsin, Carrère and Hastings' New York Public Library, Burnham's Union Station in Washington, John Bakewell Jr. and Arthur Brown Jr.'s San Francisco City Hall. Altogether, it was enough for a classicist like Henry Hope Reed to refer to the period as the 'American Renaissance'. One essential part of the program never caught on. Height limits, first employed perhaps around Copley Square in Boston, echoed contemporary practices in Europe, as in Baron Haussmann's Paris. Daniel Burnham was always adamant about them; the anarchic city of commerce was to be visually restrained and subordinate to the civic ensemble at the center. But height limits would be enacted in few places outside Washington, leaving the capital as the only city to fully capture the City Beautiful aesthetic. Opposition to skyscrapers could be fierce and occasionally cranky among the idealists. Burnham's Chicago Plan envisaged their eventual demolition, and New York's Architectural League proposed outlawing them in 1894, claiming that not only were they eyesores, but they caused malaria. The classical influence also brought some remarkable formal parks in this period: around the lagoon in Cleveland's Wade Park, or the lovely Italian garden of Meridian Hill Park in Washington. The creation of new parks and parkways continued. Indeed, this effort that began in the 80's and 90's had been at least as important as the Exposition in inciting cities to plan and build. The pioneers, Minneapolis, Kansas City and Boston, continued their far-flung systems, and their example spread to scores of other towns. Other movements from the past decades continued, too; cities improved their water and sewage systems, passed smoke abatement ordinances and codes to improve tenement housing. They started hiding their utility cables underground. The 'Civic Improvement Associations'—by 1905 there were over 2400 of them—fought billboards, installed litter baskets, and worked for as much beautification as the traffic could bear. The movement for planning continued apace; 1909 brought the First National Conference on City Planning, held in Washington. There was always more to the City Beautiful idea than grand civic centers; as the counterpart of the Progressive drive for political and social reform, it made up the more visible side of America's first broad-based quality of life movement. In general it was non-partisan, and whether businessmen, mayors or bosses got the ball rolling there was always plenty of grass-roots input, fueled by popular books such as Charles Mulford Robinson's The Improvement of Towns and Cities in 1900, and Modern Civic Art, or the City Made Beautiful, in 1903. The public had to have its say; big improvements meant big bond issues. Chicago had shown how to get them passed: public relations, models and plans, banquets and especially newspaper campaigns, an essential part of the story since William Rockhill Nelson boosted the park plan in his Kansas City Star. The psychology of the debate may seem unusual to us now: Frederick Law Olmsted's son John Olmsted, commenting on landowners who wanted to scale down the width of one of his boulevards in Seattle, accused them of a 'lack of patriotism'—of urban patriotism. In Denver, a mayor wanted to exclude a courthouse from the civic center plan because he 'did not want the derelicts of humanity to detract from the beauty of the project' (he did not, apparently, mean lawyers). City Beautiful's sweet paradox allowed Americans to be practical and aesthetic at the same time, to be democratic elitists. The men who made and commissioned the plans, along with the voters who passed the bond issues, all wanted the very best, and they wanted it in democracy's name. |

|

|